A Rag or a Rip

Contemporary Art Tasmania, 2017

Exhibition Text by Dr. Ashley Crawford:

“Robert O'Connor: Cartographer of the Peripheral” or “The détournement of Robert O’Connor”

“What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?”

“About six inches to the mile,”

“Only six inches!” exclaimed Mein Herr. “We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country on the scale of a mile to the mile!”

– Lewis Carroll, Sylvie and Bruno Concluded.

Cartographer, archeologist, explorer, scavenger, sociologist, and resurrectionist. Robert O’Connor is all of these things. His work, like the artist himself, exudes a restless energy and a palpable curiosity. He is fascinated by maps, even when they are composed of detritus, both found and formed by O’Connor himself. He notes that cities are full of unseen histories – sites of trauma, humour, accident, neglect – and he is driven to make these visible. That which many would deride as ‘rubbish’ are gist to O’Connor’s mill. One is reminded of William Gibson’s mantra in his novel Burning Chrome: “...the street finds its own uses for things.”

O’Connor takes to the street wherever he is, from Queens in NYC to Santiago to Melbourne. But in this body of work he takes to Hobart in all its claustrophobic and retroactive wonder. Hobart is besieged by isolation, a small city on an island-state, its denizens form even smaller social and cultural cliques with their own codes and linguistics. O’Connor, like an eccentric private detective in a strange neon-noir mystery, combs the streets seeking clues to some labyrinthine underworld revolving around Brisbane Street where he both lives and works. He is clearly convinced that part of the clue revolves around the Brisbane Hotel, the home of punk rock in Hobart and, as he says, “a true time-warp/stuck-in-the-80s pub replete with sticky carpet and an array of potential health problems.”

A part of this saga revolves around the battle between the archaic – the punks, the homeless, the crazies, the prostitutes – and the well-dressed denizens – the lawyers, the architects, the developers of contemporary gentrification. With this comes the inevitable clash of slang, localised dialects and isogloss, the geographic boundaries of specific linguistic features to the point where the languages of the booze-hound and the architect become impenetrable to each other while O’Connor stealthily slides between the two. O’Connor largely eschews communicating with the yuppies and hipsters who have invaded his environs, stating clearly that he prefers to talk to the people who really live there, hear their stories, hear their language. The work is about the real Tasmania he insists. Rather than the extravaganzas of MONA, it's the art of homemade bongs, backwards convict slang, provincialism, isolation and the sheer, palpable, pleading, mute desperation that exudes from a found hand-scrawled note stating: “A MALE LIKE TO MEET A WOMAN 18-50 FRIENDSHIP OR MORE.”

In his quest, the detective O’Connor has found his share of conspiracy theories and imaginary connections worthy of The X-Files FBI agent Fox Mulder or the Twin Peaks FBI agent Dale Cooper. In Hobart FBI agent Robert O’Connor unearths a MacDonald’s receipt containing mystic information revolving around the number 187. The wily O’Connor has connected this receipt information to the advertisements that the mysterious Ivan Cerjak places in the Hobart Mercury: “What is being done about work over 29 years. $5,250, the rest ‘pinched’. 1960 until 1971. 1971 to 1996. Please do not be upset. Too many people against Ivan. Why? Keep receipts. Sgd: Ivan Cerjak” or “26 years, 30.11.2016 What group of people doing, not nice! Keep receipts. Sgd: I Cerjak.” However in the day and age of Donald Trump’s Twittering one starts to wonder if the President of the United States is in some way implicated in this giant Hobart-based conspiracy. To those outside this cabal, Cerjak and Trump make equal (non)sense.

All of which perhaps links O’Connor’s other investigation into Hobart’s Cult of Jesus. The Evangelical movement in America of course got behind Trump and it’s a fair bet many of them were carrying a reproduction of the notorious Warner Sallman portrait of Jesus. The Head of Christ, also known as the Sallman Head, is a clichéd 1940 portrait of Jesus which, in conspiracy mode, could be the cause of the rise of diabetes in Tasmania. O’Connor accurately notes that, “his stuff is so sugary it hurts your teeth.” “People have claimed to have found hidden images in the shadows on his face and folds in his robe. Thus, the picture has all of this miraculous energy to it. But it’s bullshit, and Sallman is a shister.” Shister or not, Sallman’s image is a potent meme, one that the detective in O’Connor has feverishly dissected.

Alongside the Sallman Head another, more localised cultural meme, is Cheepa who, alongside Jesus, was ubiquitous for a time in Hobart.

Cheepa the price-slashing chicken was the advertising mascot for a chain of bargain stores in Tasmania called Chickenfeed. Cheepa held a bloody red sword with an electric spark shooting off it, not unlike some Nordic god, and used to supposedly slash prices. Post- 9-11 the chain replaced the grisly sword with a single feathery finger, raised to suggest “number one in bargains.” Chickenfeed went into receivership in 2013 but abandoned stores and degrading, tattered billboards featuring Cheepa remain like morbid tombstones throughout Tasmania. Cheepa was often reproduced on mirrored glass thus O’Connor has recreated these windows so that they are never forgotten. But was Cheepa a cipher? His flattened head a mysterious graphic code for the UFO sightings so common in Tasmania? Or is Cheepa more simply a symbol of the strange nostalgia – mixed with bad taste – that O’Connor suffers from?

Cerjak, Sallman and Cheepa form an (Un)Holy Trinity in O’Connor’s quest to map a Secret History of his Island Home. Cerjak was born in Poland, Sallman in the United States and of course McDonalds is universal – thus O’Connor’s conspiracy is not just in Hobart but is in fact global

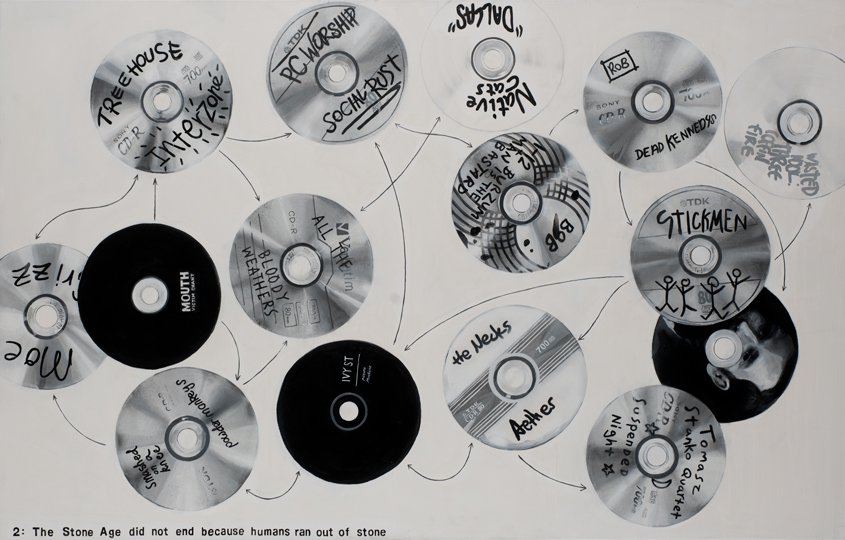

O’Connor’s recent and current work involves disused spaces and mapping the peripheral. His work can be described as falling into the realm of détournement, meaning “rerouting or hijacking,” a technique developed in the 1950s by the Letterist International and later adapted by the Situationist International. For O’Connor, this began when the artist spent time in Queens in New York City and has grown since. His recent work from Santiago in Chile resulted in large-scale paintings that documented his personal experiences of the city, specifically, he notes, the ‘peripheral’ zones. “This idea of periphery is not only physical but psychological,” he says. “The resulting ‘maps,’ as I call them, are cartographies of daily experience, intermingled with urban folklore, localised slang, seemingly inane observations from a tourist/outsider perspective.” These works were also opened up to local punk kids that O’Connor met to add their own stories, adding a patina of graffiti to the constellation of imagery. While Cheepa may have been ubiquitous in Hobart, it was knives and guns that were ubiquitous to Santiago.

Psychogeography is an approach to geography and mapping that emphasises playfulness and “drifting” around urban environments. Psychogeography was defined in 1955 by Guy Debord as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”

These works are indeed replete with emotions and behaviours, nostalgia and conspiracy amongst them. Local micro-celebrities, recordings of obscure Hobart bands, aged newspaper clippings, street graffiti and crude pamphlets – O’Connor articulates what Martin Luther King once described as the “language of the unheard.”

The Situationists gave the name dérive or “drift” to actions that would subvert the capitalist intentions of the city – in Hobart’s case, gentrification. During the Paris riots of 1968 an oft-quoted slogan was painted on the walls – “Beneath the pavement, the beach.” It wasn’t quite as romantic as it may sound – it was a reference to the sand found beneath cobblestones as they were pulled from the street by protesters to violently hurl at police. But it does sound like a reference to a paradise hidden away by surface structures and in his way Robert O’Connor is doing something similar, revealing to us the myriad riches that lie in plain sight, yet remain unseen.

Robert O’Connor, Cryptolalia 1, 2017

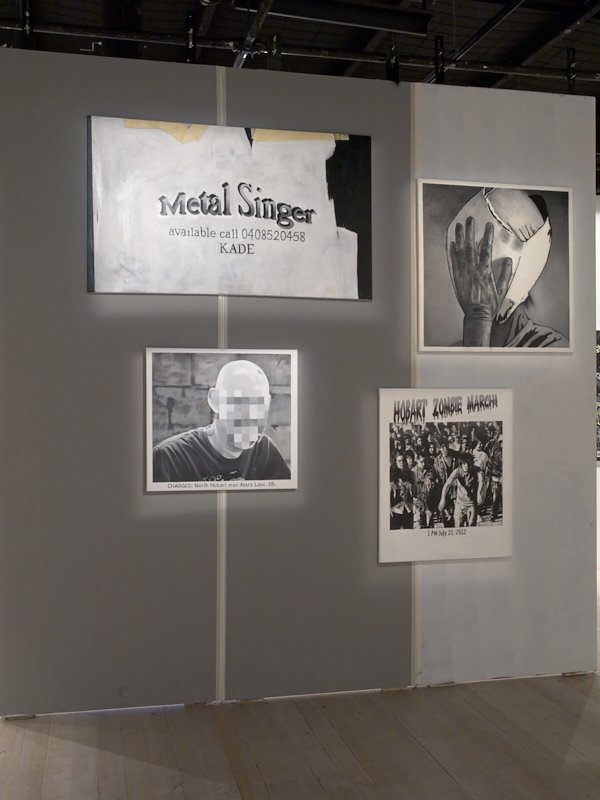

Robert O’Connor, A Rag or a Rip, installation view

Robert O’Connor, A Rag or a Rip, installation view

Robert O’Connor, A Rag or a Rip, installation view

Robert O’Connor, A Rag or a Rip, installation view